Stress-Testing a Tiny Neural Network

We often treat machine learning models as mathematical abstractions, pure functions that map inputs to outputs. We assume that if the math is correct, the system is secure. But models don’t exist in a vacuum; they run on imperfect hardware, rely on approximate floating-point arithmetic, and execute within physical constraints. I wanted to understand exactly how fragile these implicit assumptions are.

My goal wasn’t to build a high-performance classifier or to learn the basics of deep learning. Instead, I wanted to build a “glass house,” a neural network constructed entirely from scratch, without frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow to hide the cracks. By stripping away the abstractions, I could manually violate the assumptions the model relies on—data integrity, numerical precision, and execution privacy—to see exactly how and why it breaks.

The System: A Naked Implementation

I built a simple feedforward neural network using only Python and (sidenote: A popular numerical computing library in Python.) . The architecture is minimal: two input neurons, a single hidden layer of ten neurons with (sidenote: Rectified Linear Unit, an activation function that outputs zero for negative inputs and the input itself for positive inputs.) activation, and a single output neuron with a (sidenote: A sigmoid activation function maps input values to an output between 0 and 1, often used for binary classification.) activation.

The design philosophy was total visibility. There is no autograd engine; I manually derived and coded the chain rule for backpropagation. There are no optimizers hiding momentum or adaptive learning rates; just raw Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). By forcing every matrix multiplication and gradient update to be explicit, I ensured that any failure was a result of the fundamental logic, not a library bug.

Establishing a Baseline

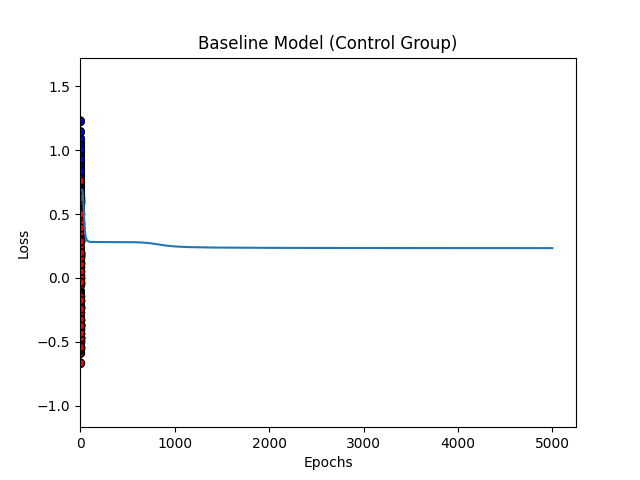

Before breaking the system, I had to prove it worked. I trained the network on a synthetic “Two Moons” dataset, two interlocking half-circles that are impossible to separate linearly. This forces the network to learn a non-linear decision boundary.

Under ideal conditions (Float64 precision, clean data, standard initialization), the network behaves exactly as expected. The loss curve drops sharply and stabilizes, and the resulting decision boundary cleanly separates the two classes. This control group confirms that the math is sound.

Breaking Data Assumptions

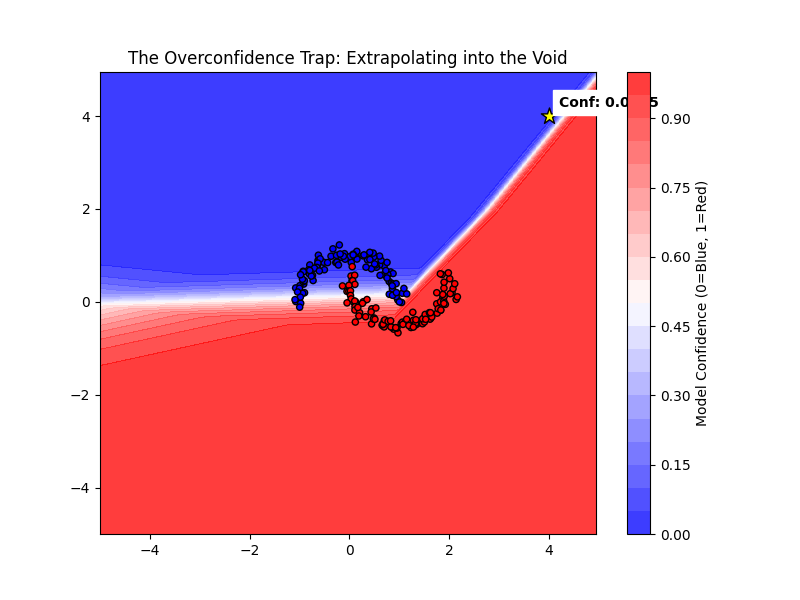

The first assumption we make is that a model knows what it doesn’t know. We assume that if a model is trained on data within a specific range, it will be hesitant or uncertain about data far outside that range.

I tested this by feeding the model a coordinate at (4, 4), far into the empty void where no training data existed. A human would look at that point and say, “I have no idea.” The model, however, extrapolated its learned decision boundary infinitely outward. It predicted “Blue” with near 100% confidence.

This happens because the ReLU and Sigmoid functions don’t have a “null” state; they essentially draw rays extending forever from the training cluster. In a security context, this means an anomaly detection system built on this architecture will confidently classify noise as signal, provided that noise sits in the wrong part of vector space.

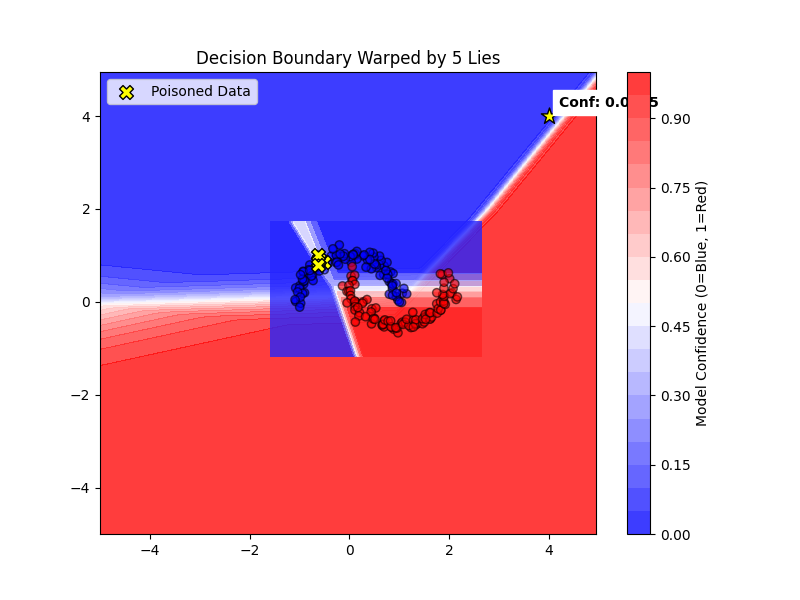

Next, I tested the assumption that the model is robust to minor data errors. I took just five data points, which is roughly 2% of the dataset, and flipped their labels, simulating a “poisoning” attack where an adversary inserts a few bad samples. I didn’t change the architecture or the hyperparameters.

The result was disproportionate damage. The smooth decision boundary warped aggressively, jutting out to capture those five lies. The model sacrificed its generalization capability to accommodate a tiny fraction of bad data. It turns out that “learning” is indistinguishable from “memorizing lies” if the optimizer is sufficiently aggressive.

Breaking Numerical Assumptions

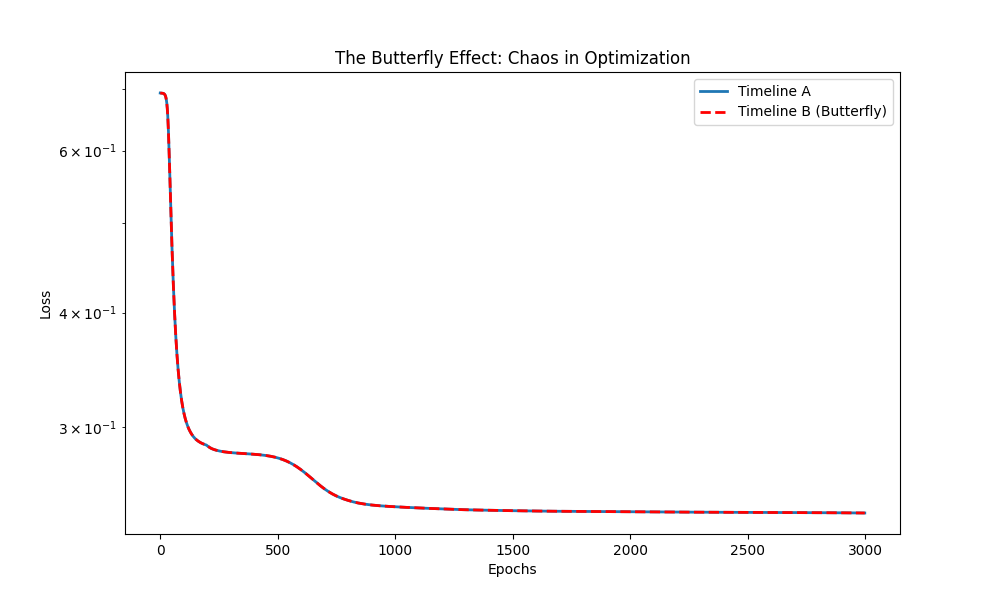

We tend to think of neural networks as mathematical abstractions that exist in a continuous realm. In reality, they are software approximations running on finite silicon. I wanted to see if the chaotic nature of floating-point math could impact the model’s destiny.

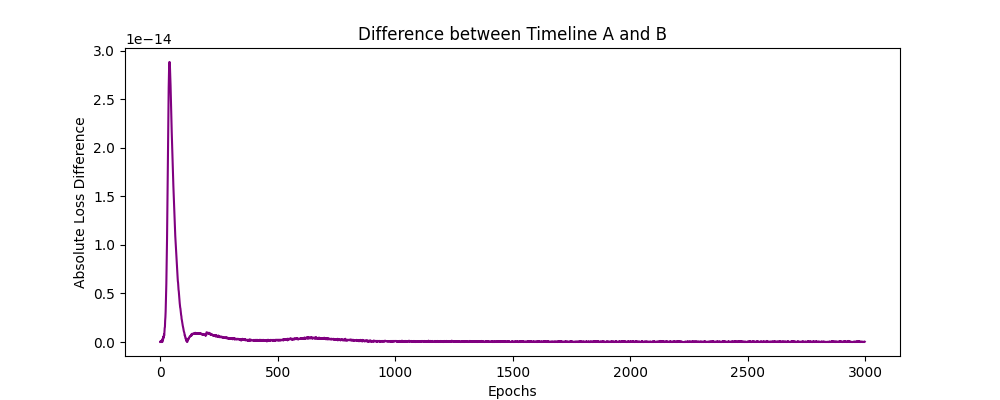

I ran two identical training timelines. In the second timeline, I added a perturbation of 1E-14, a value smaller than a single bacterium, to one weight during initialization. For the first few hundred epochs, the loss curves were identical. But then, the butterfly effect kicked in. The microscopic difference compounded through thousands of matrix multiplications, eventually causing the two models to diverge completely.

This proves that training is non-deterministic at the hardware level. You cannot guarantee that a model trained on one GPU will match a model trained on another, even with the same random seed. The “function” we are building is fluid, not solid.

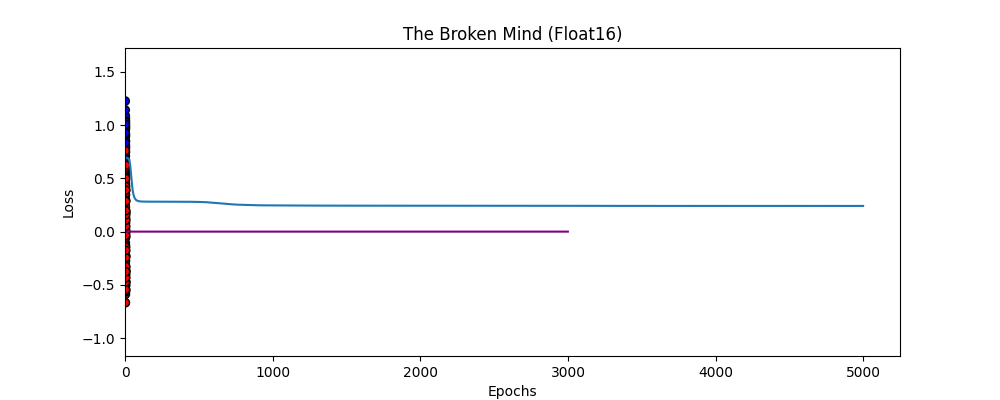

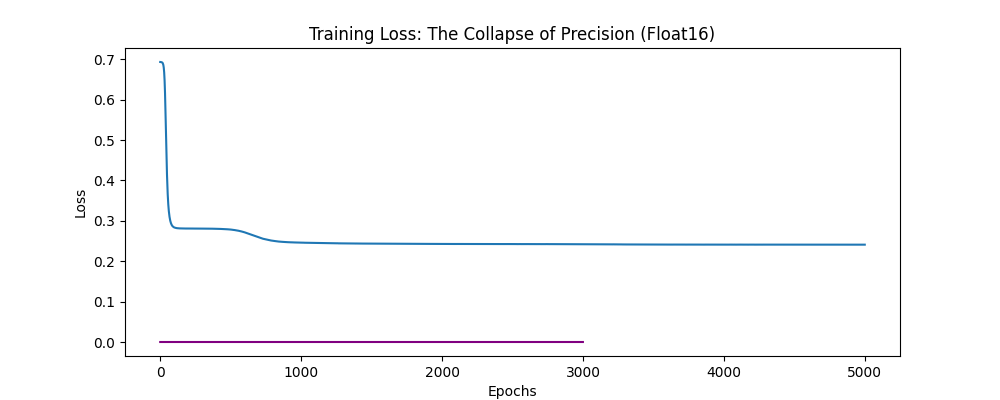

I then pushed the hardware simulation further by forcing the network to train in float16 (half-precision), mimicking the constraints of edge devices or aggressive quantization. The result was immediate brain death. The gradients, which were already small, underflowed to zero. The model stopped learning entirely, producing a flat-line loss curve. We often assume “math is math,” but this showed that the architecture is deeply coupled to the precision of the hardware it runs on.

Breaking Execution Assumptions

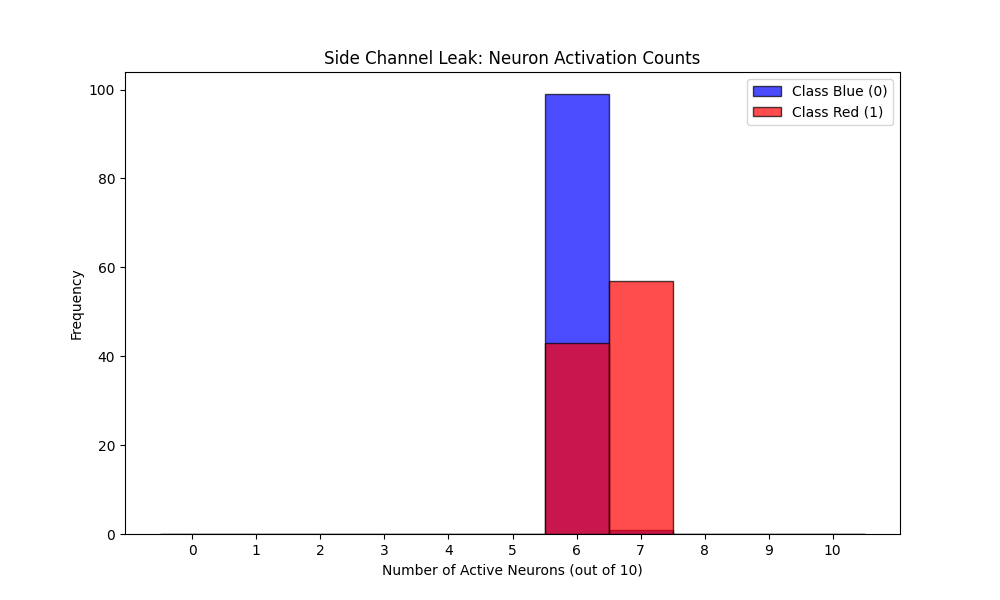

Finally, I looked at the assumption that inference is a “black box,” that when we ask the model a question, the only thing that leaves the system is the answer. I instrumented the code to count exactly how many neurons in the hidden layer fired (output a non-zero value) for each class.

The results revealed a physical information leak. When the model processed “Blue” inputs, it consistently activated an average of 6 neurons. When it processed “Red” inputs, it activated roughly 7 neurons.

This is a classic side-channel. Even without seeing the input data or the output prediction, an attacker measuring the power consumption or execution time of the processor could statistically guess which class the model was processing. The model’s “thought process” has a physical footprint that varies based on what it is thinking about.

Implications

This investigation suggests that AI security cannot be treated as a wrapper we put around a model after it is built. The vulnerabilities are structural. The overconfidence in unseen data, the sensitivity to poisoning, the dependence on numerical precision, and the side-channel leaks are not bugs; they are inherent properties of how we do matrix multiplication on silicon.

If a toy model with fewer than 50 parameters exhibits these behaviors, we must assume that billion-parameter production models inherit them at scale. We are not building abstract reasoning engines. We are building complex, chaotic software artifacts that trust their inputs implicitly and leak their internal states physically.

Open Questions

There is much this simple experiment didn’t touch. I am curious how these fragilities change with depth, does a deeper network smooth out the “poisoning” effect, or does it offer more surface area for the boundary to warp? I also wonder how normalization layers, which I omitted for simplicity, might mask or exacerbate the side-channel leaks by standardizing activation distributions.

Most importantly, I am left wondering about the trade-off between efficiency and security. The sparse activation of ReLU is what makes it efficient, but it is also exactly what created the timing leak. It seems that many of the optimizations we rely on for speed may be the very things that make our “glass boxes” transparent to adversaries.

Open Source

I’ve open-sourced the code on GitHub. Feel free to reproduce the experiments, poke at the assumptions, and build on the framework. Understanding these fragilities is the first step toward designing more robust AI systems for the future.